Recent events concerning Greenland demonstrate that the European foreign policy of placating rather than standing up to US President Donald Trump may have backfired. In a world of Trump, Putin and Xi, the weak are preyed upon despite shared values and history. Europe is demonstrably seen as weak in Washington and hence subject to further extraction. The crisis of Greenland is a crisis of European identity.

The “Tariff King” strikes again

The Greenland crisis escalated further this past Saturday. Trump has repeatedly insisted that the US ought to own Greenland and has made clear his willingness to purchase or ascertain the island by other means. Trump made overtures in his previous administration in 2019, but this time around there has been a clear switch of tone. Denmark and Greenland have both made clear that Greenland is not for sale and that they are more than willing to accommodate US security or strategic resource demands.

In an ironic twist, eight European nations—Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Norway, Germany, France, the UK, and the Netherlands—landed troops in Greenland under "Operation Arctic Endurance." At least on paper, the move was designed to address a key US concern: that Europe was not able to handle the security of Greenland. Instead, Trump interpreted the move as defiance and used it as a pretext to ramp up pressure.

On Saturday, an incensed Trump issued escalating tariffs against these eight European nations until a deal for the full acquisition of Greenland is signed. Tariffs begin at 10 percent on February 1, 2026, and automatically jump to 25 percent on June 1, 2026, if no "purchase agreement" is reached.

The Truman show: Greenland as a Nuclear Bomber Base

This is not the first time Greenland has been the center of geopolitical wrangling. After the Second World War, the US under President Harry S. Truman realized that in the case of a nuclear war with the Soviet Union, the shortest distance between the two powers was to fly bomber planes across Greenland. Hence, the US needed Greenland to support its bomber fleet and as a means of detecting and shooting down Soviet bombers.

The US secretly offered Denmark $100 million in gold bullion for the island. Then, as now, Denmark flatly rejected the purchase. Also then, as now, Denmark was more than willing to address US military concerns. The 1951 Defense of Greenland Agreement allowed the US to establish "defense areas," most notably Thule Air Base (now Pituffik Space Base), and granted the US permanent military access and security control.

At the peak in the late 1950s and 1960s, following the construction of Thule, there were 10,000 to 12,000 US troops in Greenland operating 17 major bases. Greenland served as the primary refueling and staging point for nuclear-armed B-52 bombers. Technology and intercontinental missiles eventually replaced bomber fleets; today, there are roughly 150–200 US personnel in Greenland.

US motivations: the Golden Dome and strategic resources

The US case for Greenland is twofold: security and strategic resources. In terms of security, the role of Greenland has transformed from a floating bomber base to a vital node of the missile defense system. Just as Denmark accommodated Truman’s needs for defense, it is clear that Denmark and Greenland are willing to accommodate Trump’s needs. In fact, Greenland’s stagnant economy would likely relish the infrastructure boost from the US building radar stations and interceptor silos.

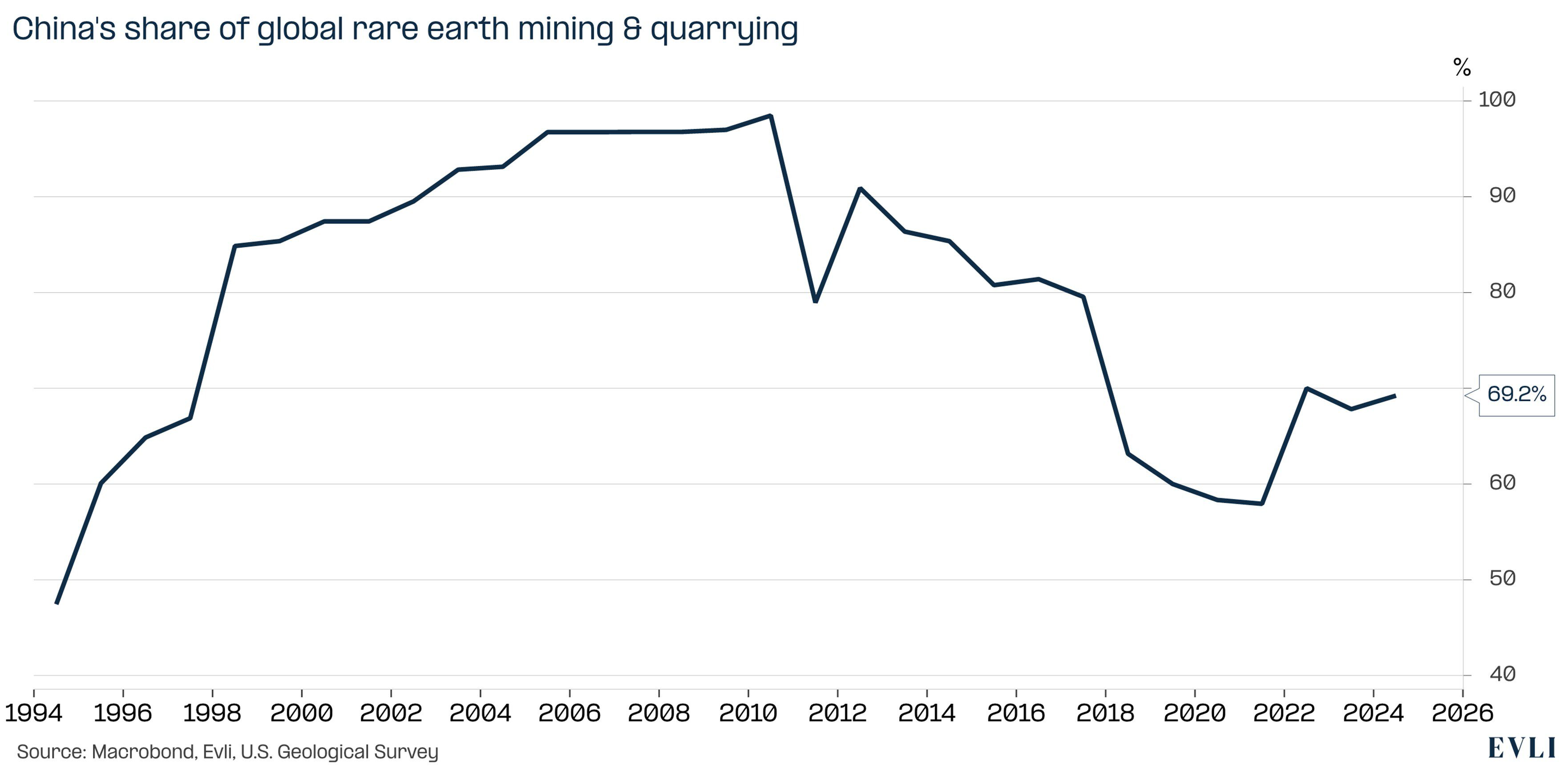

The US also wants Greenland for its strategic resources. China’s share of global rare earth mining and quarrying is about 70 percent, a position it leveraged against the US during the second trade war of 2025. Greenland is a source of 31 out of 34 critical minerals.

The US insists that it wants to deny China the ability to develop rare earth minerals in Greenland. There are currently two massive, non-operational mining sites: the US-backed Tanbreez and the Chinese-linked Kvanefjeld. However, the US has already been able to block the Chinese site from proceeding by having Greenland stop the project on the grounds that the site is rich in uranium. Greenland has thus already displayed that the US can obstruct rivals if it wishes to do so.

Figure 1: China’s share of global rare earth mining & quarrying is about 70 percent

A constituency of one

In political economy, political actors cater to the wishes of a specific constituency. But in the case of Greenland, it is hard to find any relevant constituency that supports a takeover, especially if it involves using force. Across polls from Quinnipiac, ABC News, and Ipsos, 86–91 percent of Americans oppose using military force to take Greenland. Within the MAGA movement, most support America First, which traditionally means not getting entangled in foreign escapades.

It may very well be that the only part wishing to take over Greenland is Trump himself. Since US security and strategic demands can already be accommodated, his motive may simply be legacy. He wants to put his mark on history by adding a giant piece of territory to the United States. Since he has failed to entice Canada, Greenland may be the next best thing.

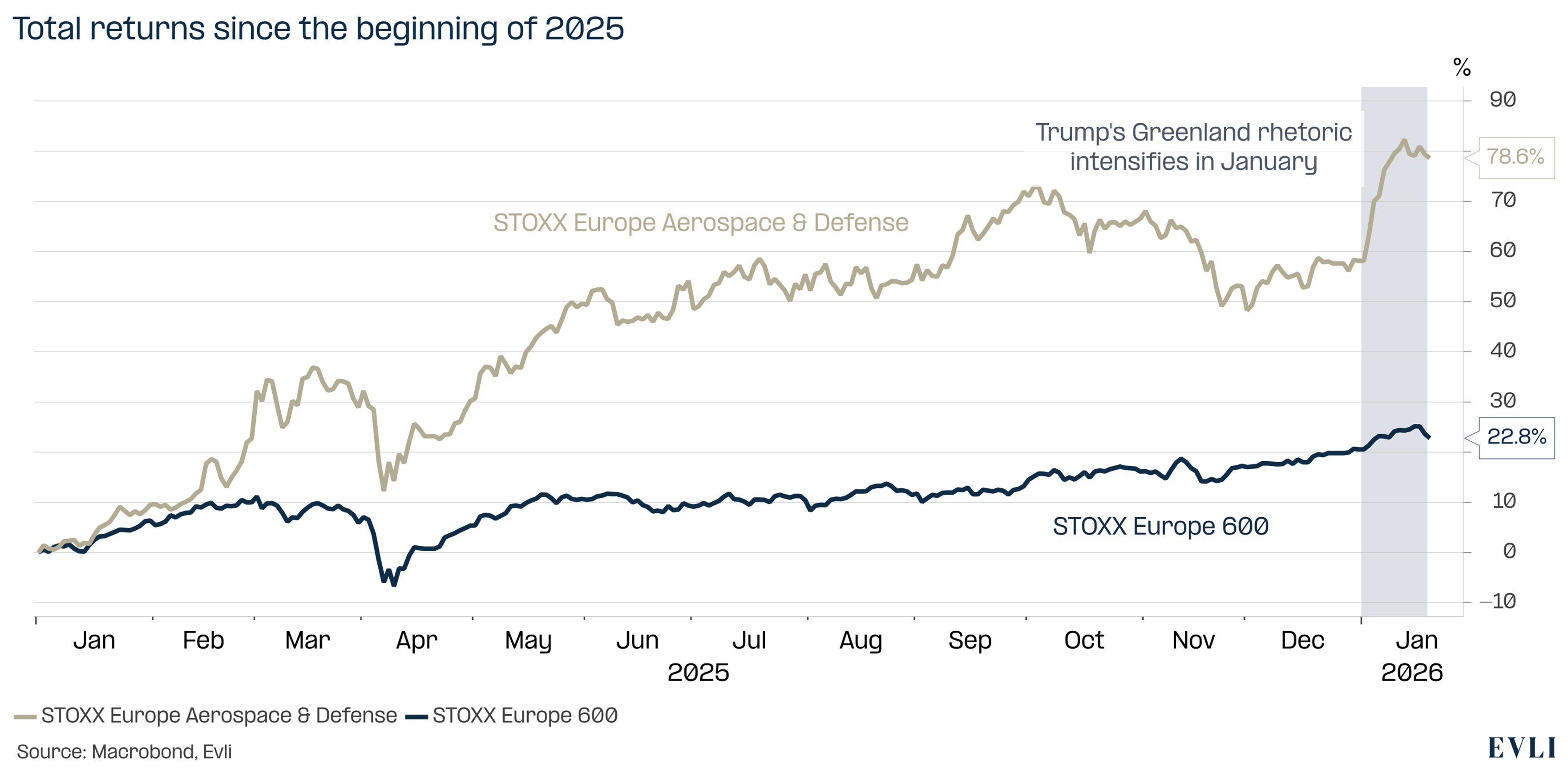

Figure 2: The European Aerospace & Defense sector has outperformed the market

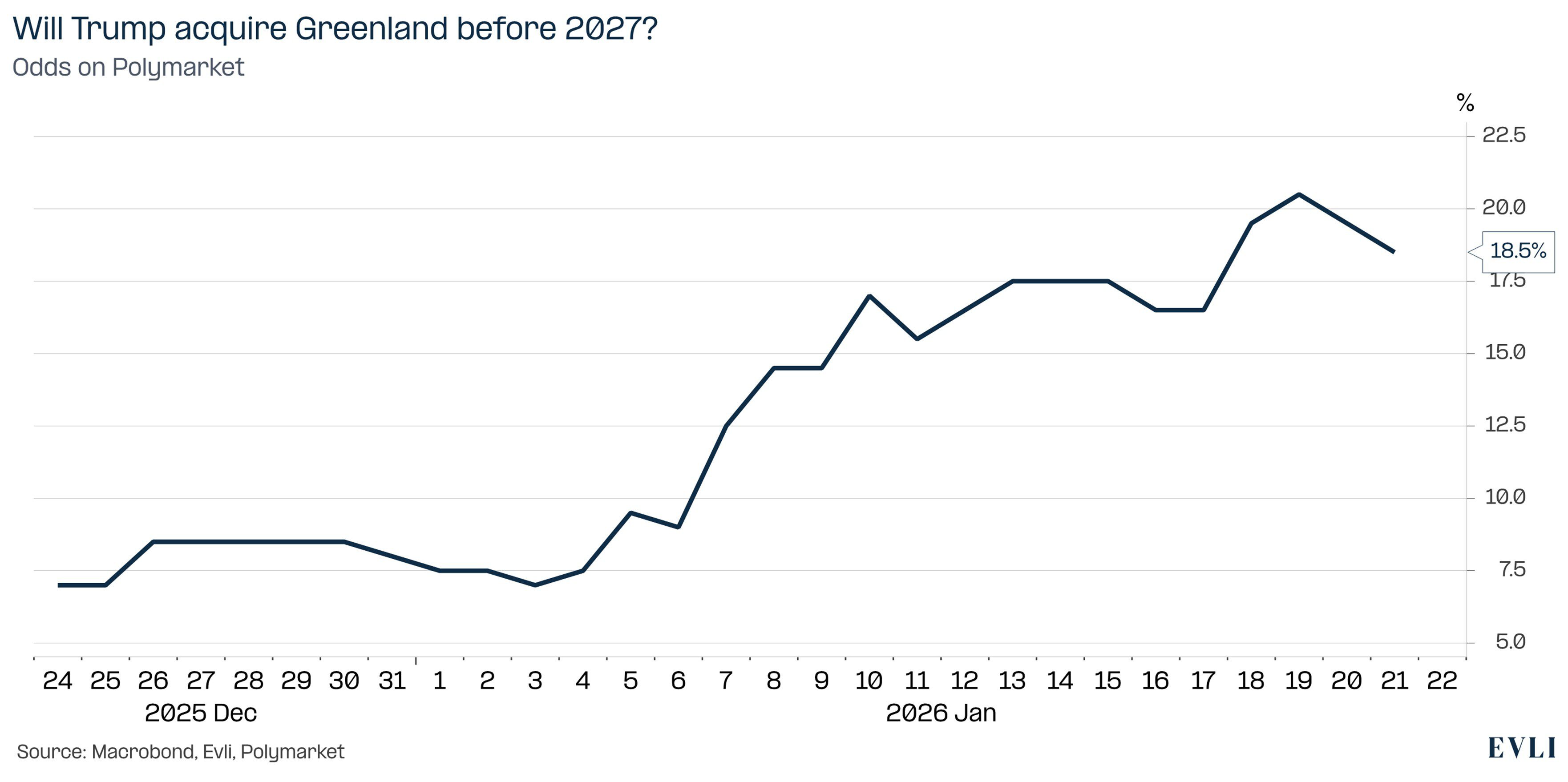

Figure 3: The market-implied probability that the United States will acquire Greenland has increased since December

Europe pushed to a breaking point

The European policy of appeasing Trump appears to have failed. Europe was willing to accommodate Trump and avoid a trade war out of fear that the US might pull support for Ukraine. Europe may now be paying the price for appearing weak, and Trump has come back for more.

Europe now faces a starker choice than during the trade war: Should Europe push a smaller member state to cede territory? This line of policy harks back to a darker age in Europe’s history. According to a poll by the research institute Verian in January 2025, 85 percent of Greenlanders oppose joining the US. Europeans would be signing away territory against the will of its inhabitants.

The end of Nato and a new Europe?

Giving away member state territory would damage the credibility of both Nato and the EU. For this very reason, the EU is unlikely to give away Greenland, and Trump has reached too far. On the economic front Europe has plenty to retaliate with but will likely first engage in a bout of diplomacy before the February 1 deadline. If it chooses to retaliate, the EU can delay US-EU trade deals, impose counter-tariffs, or invoke the Anti-Coercion Instrument to target US technology firms.

The most likely outcome in this bizarre game is Trump backing off after a deal which leaves Greenland intact but provides Trump with the appearance of victory. Europeans would be more than willing to provide the US with a deal that satisfies US security and resource demands.

The US is unlikely to invade Greenland since there is no political support for invading a fellow Nato country. However, the possibility though small is still within the realm of possibility. And should the US invade Greenland it would mean the end of Nato and cause a rift between the US and Europe that would have profound implications for Europe. It might just finally unite Europe.