In 2008, the EU and US economies were roughly the same size. Now, the US economy is 50 percent larger. What happened? A common narrative relies on Europe’s inability to navigate the technological transformations marked by the internet and the cloud. If so, history may repeat itself as we transition through artificial intelligence. However, there are problems with the simple technological transition narrative.

Les trente glorieuses

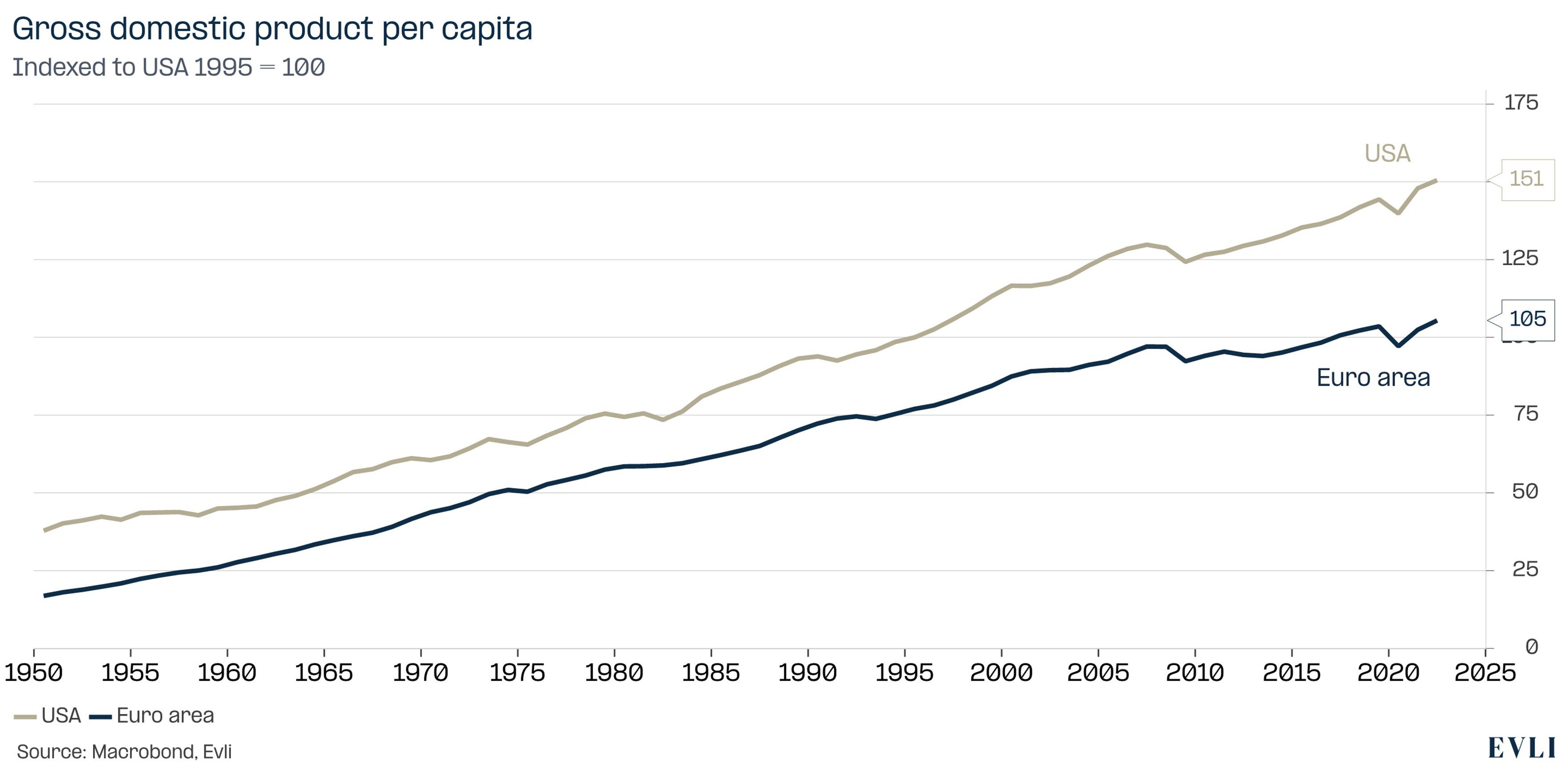

In the 1950s, '60s, and '70s, the European economy grew significantly faster than the more advanced US economy. This rapid growth was driven partly by post-war reconstruction and partly by Europe’s ability to utilize technology already developed in the US. Standard economic theory holds that poorer economies "catch up" to richer ones by copying them, whereas advanced economies face the harder task of developing new technologies. Growth is naturally faster the further one is from the bleeding edge of innovation.

Figure 1: The euro area economy grew faster than that of the United States in the 1950s-70s

Going on vacation

By the 1980s, European economic growth slowed compared to the United States. This slowdown, however, largely resulted from a preference for leisure over work, while Americans maintained their working hours. By the 1990s, Germany and France had caught up to and even surpassed the US in productivity.

Europe had never had it so good: economically, it rivalled the US, and on the security front, the Soviet Union collapsed. This allowed Western Europe to cut defense spending and enabled Eastern European nations—led by pro-democracy figures of the era like the Hungarian politician Viktor Orbán—to strengthen the European Union.

Mind the gap

Starting in 1995 and accelerating after the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, the US economy pulled away. In 2008, the EU and US economies were roughly equal, but by 2024, the US economy was 50 percent larger, despite having a population of 342 million compared to the EU’s 450 million.

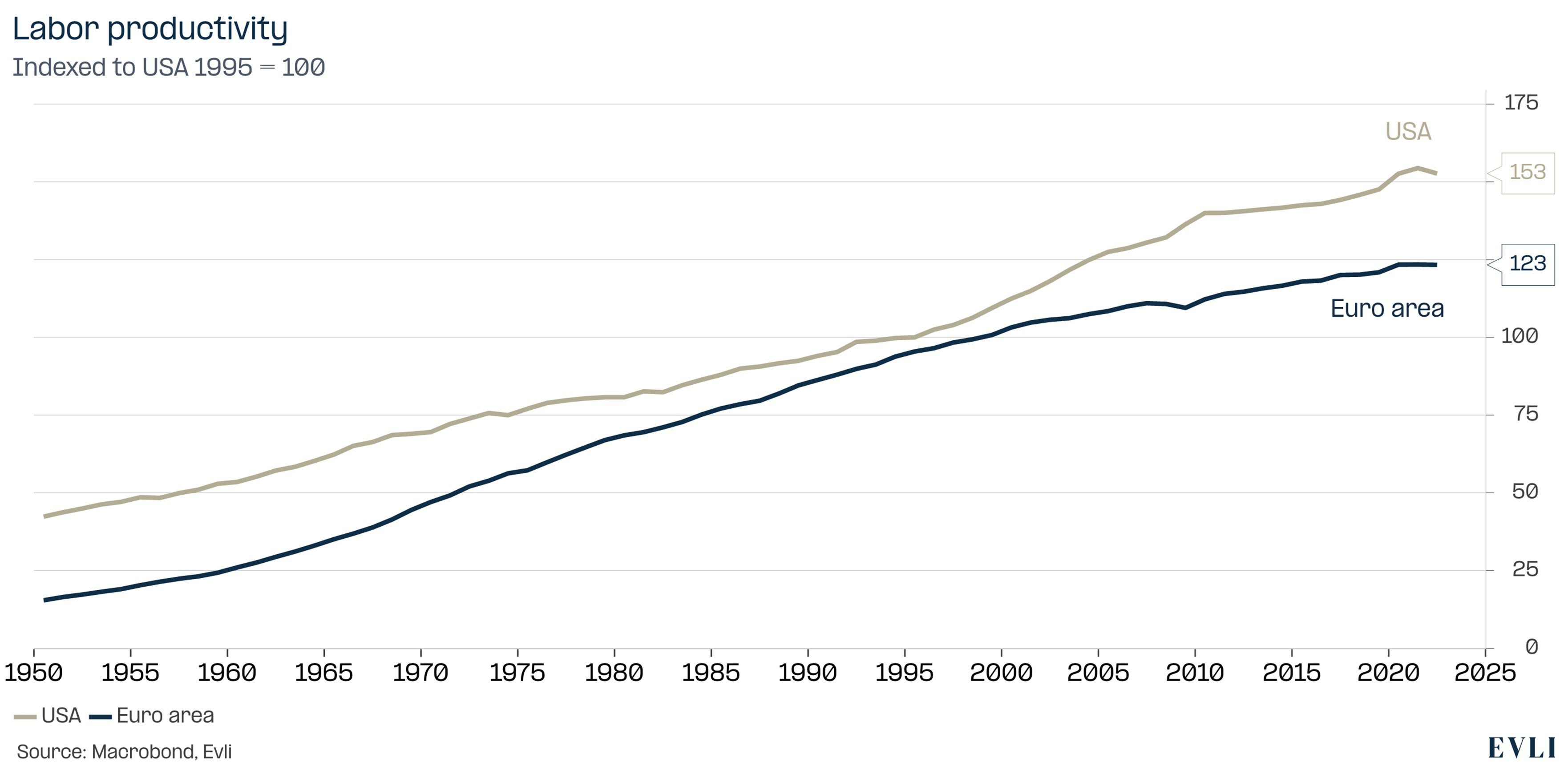

Europe’s economy has lagged primarily due to slower productivity growth. This is worrying, as productivity is the only source of economic growth that involves no trade-offs. One can visualize the economy as a factory: increasing workers or hours per worker boosts GDP but demands more labour or detracts from leisure; increasing productivity involves no trade-off.

Figure 2: Since 1995, labor productivity has grown faster in the United States than in the euro area

Talkin' 'bout a revolution

The Draghi report (September 2024) notes that while EU productivity was 95 percent of the US level in 1995, it fell to 80 percent by 2023. Mario Draghi, former President of the European Central Bank, identifies Europe’s failure to adapt to the modern economy as the main culprit. Europe’s incentive structure failed to capitalize on the internet, software, and cloud computing transitions.

Draghi’s indictment is particularly damning as the world is braced for a second transition driven by artificial intelligence. Since Europe lacks a strong technological edifice from the first revolution, it is likely to miss the second. The current builders of AI infrastructure—Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon—are the clear winners of the previous internet transition.

Mid-tech trap, energy prices, and the less-than-single market

Draghi argues Europe is stuck in a “middle technology trap”. Europe excels in mature technologies like combustion engines and traditional pharma, where the scope for productivity gains is limited. Furthermore, China has matured from producing T-shirts to becoming a leading competitor in automobiles and pharmaceuticals, intensifying competition in these sectors.

Energy also plays a role: while the shale revolution turned the US into a net energy exporter and enabled inexpensive domestic energy, Europe relied on a hybrid strategy of renewables and cheap Russian natural gas. Consequently, EU companies now pay much higher energy prices than their US and Chinese competitors.

The European single market is not truly unified. While goods trade in a common market, services do not. Crucially, European capital markets remain 27 distinct markets rather than one, rendering financing expensive. Regulations often force companies to tackle 27 separate jurisdictions. Europe also suffers from higher taxation, more regulation, and market fragmentation.

This fragmentation is reflected in the fact that most member states maintain their own banks, insurers, utilities, and defense operators. Consequently, companies fail to achieve the scale necessary to fund massive infrastructure projects, such as the AI datacenter ramp-up seen in the US.

The problem with the technological explanation of underperformance

The idea that Europe lags economically because it missed the tech transition is intuitively appealing. Aside from ASML and SAP, Europe lacks modern tech giants, whereas the US list reads like a phonebook. The US technology ecosystem is a flywheel composed of leading technology companies, a highly skilled and attractive labour market, and a deep pool of capital. The US ecosystem was not developed overnight; rather, it began in the 1960s as the US semiconductor industry grew to supply the US military-industrial complex. Today, technology makes up roughly 40 percent of the S&P 500, compared to just 5 percent in Europe and over 20 percent in Emerging Markets.

However, the problem with this simple narrative of US technological superiority is that the macroeconomic benefits of technology should flow to European and Asian users regardless of where the company is headquartered. While profits flow to US investors, productivity gains from the internet and cloud should flow to the users of these products. European companies use the same unintuitive and bug-filled software products offered by Microsoft. Consumers around the world watch the same AI-generated cat videos.

European identity continues to be national

Fundamentally, Europe’s problem is political fragmentation, which results in economic fragmentation. European policies are the result of bargaining between 27 sovereign states, rarely leading to an optimal outcome for the Union as a whole.

One might have expected the re-emergence of Trump and a hostile Putin to force European states into a more holistic strategy. In defence, Europeans have made progress. However, in economic policy, Europe continues to be divided. Take, for instance, Chinese automobile imports: France wants to block them to protect local manufacturing, while Germany opposes blocking them for fear of losing market share in China.

Fundamentally, European fragmentation may reflect the fact that Europeans are not "Europeans," but rather Germans, French, and so forth. Hence, there is support for politicians lobbying national policy over European policy. Local identity dominates a common European identity. An American identity was the outcome of centuries of immigration that diluted national identities. The English language displaced other languages, which further eroded national identities.

Europe is unlikely to change

European countries are more homogenous and oppose significant further immigration. Hence, it is hard to see Europeans overcoming local preferences. And even if Europe were a single political entity, it might end up as a large Belgium where power would remain in regional hands. In any case, it is hard to see European fragmentation disappearing in the near future.

However, the question remains: why is fragmentation particularly problematic right now? Europe grew rapidly for four decades, even though our culture was hardly significantly more unified back then.

Perhaps the explanation lies in the fact that in the era of the digital economy and the internet, a fragmented structure is toxic in a way it was not during the age of the combustion engine. Network effects and economies of scale are more important than before. It is difficult to give a single, simple explanation for the European " drag," but the change in era is certainly one culprit.